-

Know more about the artist

This week, we invite you to discover Untitled, a work by Dalila Dalléas Bouzar, a Franco-Algerian artist born in Oran in 1974.

Delphine Lopez, director of the Galerie Cécile Fakhoury in Dakar, offers us a personal reading of this work. -

When I sat down at my desk-dining table to start writing this text, I've been confined at home for exactly 28 and a hlaf days, 684 hours, 41,040 minutes, 533,520 breathings cycles if you consider my personal average is 13 breathing cycles per minue, 1,026,000 blinks if you consider my personal average is 25 blinks per minute given the recent increase in my anxiety level. When I sit at my desk-dining table, I don't know much about Untitled, this work by Dalila Dalléas Bouzar done with coloured pencils on paper in 2011, 7 years before I started working at the gallery, 2,555 days, 61,320 hours, 47,829,600 breathing cycles, always according to the same average.

Today (tomorrow is another story), I like the idea of not knowing; of starting to write out the void, as one would launch the unbridled gearwheels of the imaginaton to see (just in case) where it leads us. I would call this text out of the void Topographies fantasmées d'un salon [Fantasized topographies of a living room]. It would be a work of fiction which plot would unfold as follows: a woman is forced to stay at home because the world is gnawed by an evil that it has created and cannot yet get rid of. For part of the planet, the concept of life has given way to that of survival. For the other, nothing has really changed, except perhaps that it looks more circumspectly at the other side struggling. Everywhere, opinion oscillates with deleterious insolence between an ode to instantaneous enjoyment and the vain exorcism of a tomorrow without a future.

At home, lying on her couch where she noticed for the first time in two years (she doesn't often sit on it) that the seat of the second cushion is slightly convex, the woman is looking at a work she hung on the wall 7 months earlier; 213 days if we include the fact that the year is leap year, 306; 720 minutes; 7,668,000 blinks if we consider that her personal average is 25 blinks per minute given the recent increase in her anxiety level. It took her precisely 22 minutes to complete the work, and it was just as difficult to hang it on the wall given the thickness of the colonial buildings built in Dakar in the 1960s. The work in question is called Untitled and was painted by the French and Algerian artist Dalila Dalléas Bouzar in 2011. It measures 70 cm high by 100 cm long, a size that was decisive in her decision to acquire the said work 8 months earlier, allowing her, according to the laws of the art market, to buy it at a price corresponding to her budget andto be able to hang it in her 50 square meter in Dakar with one third of the view of the sea. When she sent the picture of the work to her mother, as she does almost every time she buys something important in her life, her mother told her: "a mineral enclosure in an overcrowded city". Her friend Mika, who does not especially understand the work and with whom she almost never agrees, told her: "I see a flood".

-

By dint of contemplating Untitled, motionless in her couch, the spatial landmarks become blurred. Her body, inert for a while, is numb. The border between her skin and the fabric is imperceptible, moving, fluid. As sometimes in yoga, when she succeeds in creating a perfect synchronization between her breath and her movements, she feels this strange effect of decentering, or rather of " splitting of the self into delocalized entities " as if she were beyond time and space and yet well inscribed in the course of time - " deictic ". She begins to think out of the void, as she would launch the unbridled gearwheels of her imagination, to see (just in case) where it leads her. At the same time, she knows that this may not be the time to plunge into the void, because for her, the void is only to be explored through the overflow that surrounds it; which is far from being the case at this precise moment since the world has emptied itself, the city is empty, the street is too. Somewhere, the work she contemplates represents this emptiness. In this paradox specific to painting, she thinks, a work does not need to be empty to show emptiness. Its materialistic existence, in and of matter (pigments, paint, ink, felt-tip pen, pencil) can purposefully serve the representation of nothingness. So Untitled shows this space, an interior space of which she sees only one angle, the drawing of a 2-dimensional angle from which her brain strives to reconstitute the whole room (in 3 dimensions) so much so that she understands for the first time that the viewer's point of view is within the space, enclosed between the four walls, two of which will always be behind her. To such an extent that, suddenly conscious of being in her turn caught between these four walls of the image, seized by a sort of metaphysical vertigo, she stretches out an arm to check that the wall at the head of her sofa is indeed the wall of her apartment.

Untitled is a mental space, she says to herself. The artist has represented an interior, the interior of something, a house, an apartment, in short, a physical space recognizable and distinct from me. Yet when I look at the work an adhesion is created between this space and my inner self in such a way that I project into the image all that I have in me; unless it is the image that projects into me what I have in me anyway. Here the colours are malleable, wadded materials. They silently take the form of the thoughts that pass through them, from the most structured idea to the most shapeless principle, memories or nightmares; a latent pink stain; a burst or blackness in the making. About architecture, she then thinks about what someone said to her recently, she can't remember who: "All architecture is ideology. Like everything else, architecture is an apparatus". So would Untitled be the representation of an apparatus? A complex apparatus that we think is our own, intimate, and created by us; that we claim as such, but which in reality would pre-exist us as most of our living interiors pre-exist, the embodied depositories of the stories of others; of everyone's stories, and of the progress of ideas and their downfall? She read in an exhibition booklet one day at the Musée du Quai Branly, where the artist was doing a performance, that Dalila Dalléas Bouzar builds her plastic reflection in a permanent dialogue with History, a critical aesthetic approach that aims to re-inscribe in a regime of visibility that and those that the world race deliberately leaves in the shadows. Then, in the liquidity of the black flat (finally the link with the flood of his friend Mika?), in the toxico-erotic radiations of the pink stain, the budding, anguished idea that one would be nowhere at home and especially not at this moment when home is defined only by the imposed external constraint and the supposedly salutary exclusion of the essential danger of living in an organic world. An organic world, moreover, which we shape with great strokes of "at home" and "elsewhere", of "self" and "other", whose justifications would certainly require re-examination. The concept of a "room of one's own", as one can read on the edge of one of the books in her bookshelf, is shattered: the biopolitical device would also, and perhaps above all, integrate the home. She shivers. For her, the mise en abîme is vertiginous (NB: Suzanne thinks that mise en abîme vertigineuse is redundant. She is probably right). Doubt invades her, the rhetoric of her thoughts is thrown into the void but she sees (already) where it leads her. Maybe I should call the gallery to put me in touch with the artist who would explain her approach, she thinks, at least that would be safe. She wiggles her toes, her feet, the tips of her fingers and gets back in touch with her body. She looks at the time, no doubt about it: 11:01 p.m. - 1,410 minutes, 18,330 breathing cycles, 35,250 potential daily blinks.

-

-

Available Works

-

Dalila Dalléas Bouzar, Time of Massaker, Série Topographie des Terrors, 2013

Dalila Dalléas Bouzar, Time of Massaker, Série Topographie des Terrors, 2013 -

Dalila Dalléas Bouzar, Sachsenhausen, Série Topographie des Terrors, 2013

Dalila Dalléas Bouzar, Sachsenhausen, Série Topographie des Terrors, 2013 -

Dalila Dalléas Bouzar, Untitled #2, série Topographie des terrors, 2013

Dalila Dalléas Bouzar, Untitled #2, série Topographie des terrors, 2013 -

Dalila Dalléas Bouzar, Untitled, Série Topographie des Terrors, 2013

Dalila Dalléas Bouzar, Untitled, Série Topographie des Terrors, 2013 -

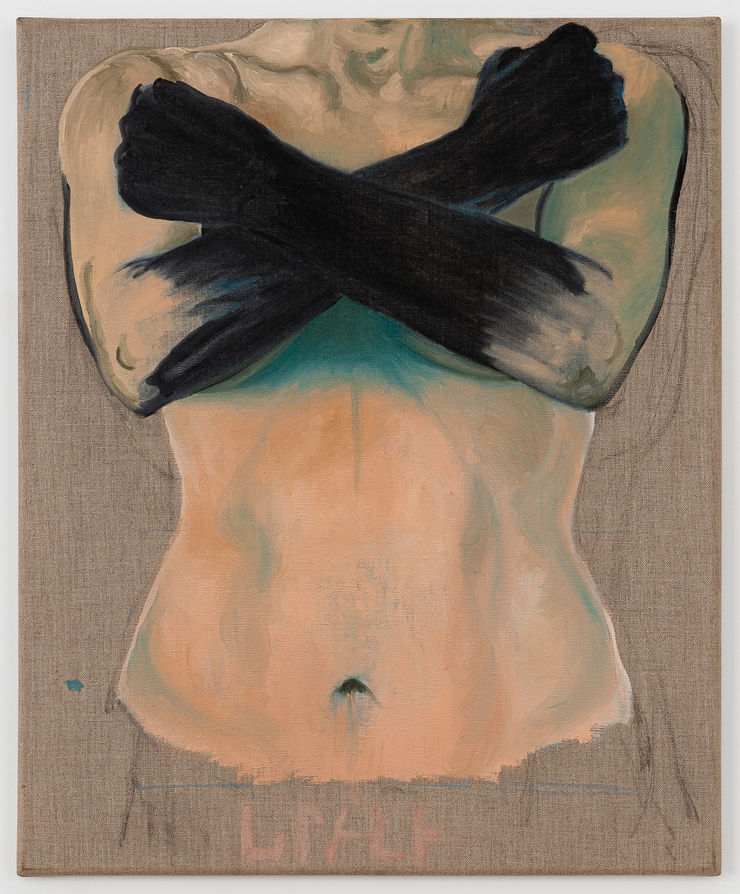

Dalila Dalléas Bouzar, Autoportrait #3, 2018

Dalila Dalléas Bouzar, Autoportrait #3, 2018 -

Dalila Dalléas Bouzar, Untitled #1, série Rencontre, 29,7 x 21 cm, 2019

-

Dalila Dalléas Bouzar, Untitled #6, série Maison, 2016

Dalila Dalléas Bouzar, Untitled #6, série Maison, 2016 -

Dalila Dalléas Bouzar, Untitled #4, série Maison, 2016

Dalila Dalléas Bouzar, Untitled #4, série Maison, 2016 -

Dalila Dalléas Bouzar, Untitled #11, série Maison, 2016

Dalila Dalléas Bouzar, Untitled #11, série Maison, 2016 -

Dalila Dalléas Bouzar, Ma demeure #8, 2019

Dalila Dalléas Bouzar, Ma demeure #8, 2019 -

Dalila Dalléas Bouzar, Untitled #7, série Ma demeure, 2019

Dalila Dalléas Bouzar, Untitled #7, série Ma demeure, 2019 -

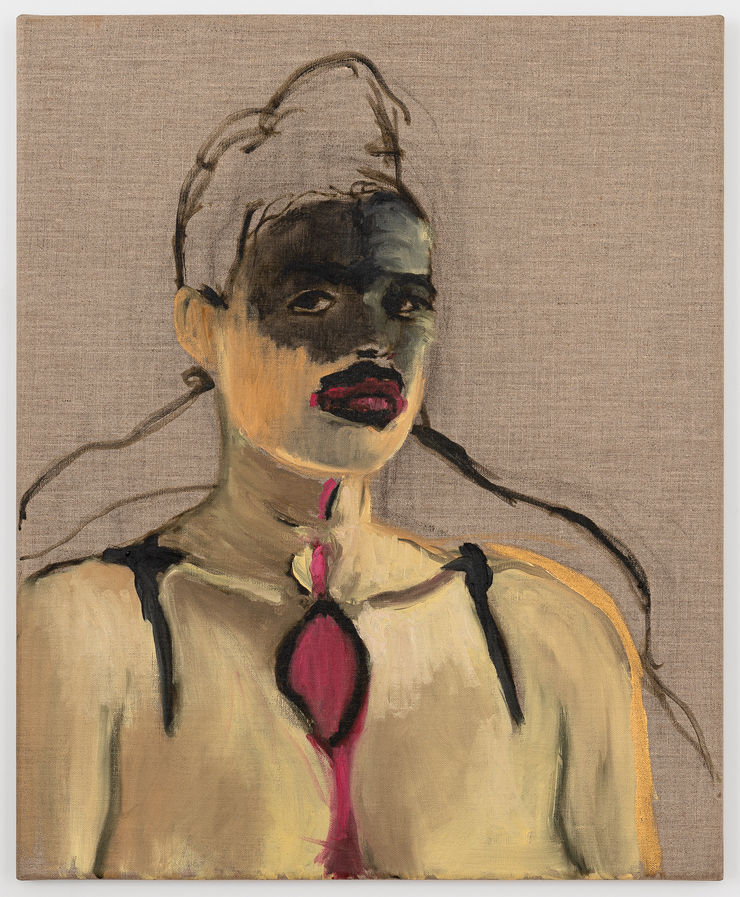

Dalila Dalléas Bouzar, Studio Dakar (Mbaye), 2018

Dalila Dalléas Bouzar, Studio Dakar (Mbaye), 2018 -

Dalila Dalléas Bouzar, Elom, 2018

Dalila Dalléas Bouzar, Elom, 2018 -

Dalila Dalléas Bouzar, Sorcières #11, 2019

Dalila Dalléas Bouzar, Sorcières #11, 2019 -

Dalila Dalléas Bouzar, Sorcières #12, 2019

Dalila Dalléas Bouzar, Sorcières #12, 2019

-

Focus sur / Untitled, 2013, Dalila Dalléas Bouzar: Partez à la rencontre du travail d'un artiste à travers l'analyse d'une de ses œuvres

Past viewing_room